How to identify 21 ways our emotions are deceiving us

I wanted to write about the complicated, time-consuming, and often repetitive process of untangling our emotions and understanding what’s really going on inside our minds, especially when we’re trying to find our way out of anxiety and depression.

And I’ll admit I was again about to use my old ‘peeling an onion metaphor’, which you might have seen in other articles here on deliberate.one.

I have often examined an emotion of mine and discovered something else underneath. “I’m angry. Let’s peel it off and see… oh, I’m sad; that’s what I really am. Oh no, there’s something more under here; I feel humiliated…” Hence, the metaphor of peeling layer by layer off an onion.

Then, I suddenly realised I might be about to oversimplify this topic for you. It isn’t always a systematic and straightforward process to determine what we truly feel. It’s not like my childhood expeditions to the beach, where I would simply lift stone after stone to look for crabs.

I decided to conduct some research to find a more suitable vocabulary to describe the misty landscape of our hidden and disguised emotions.

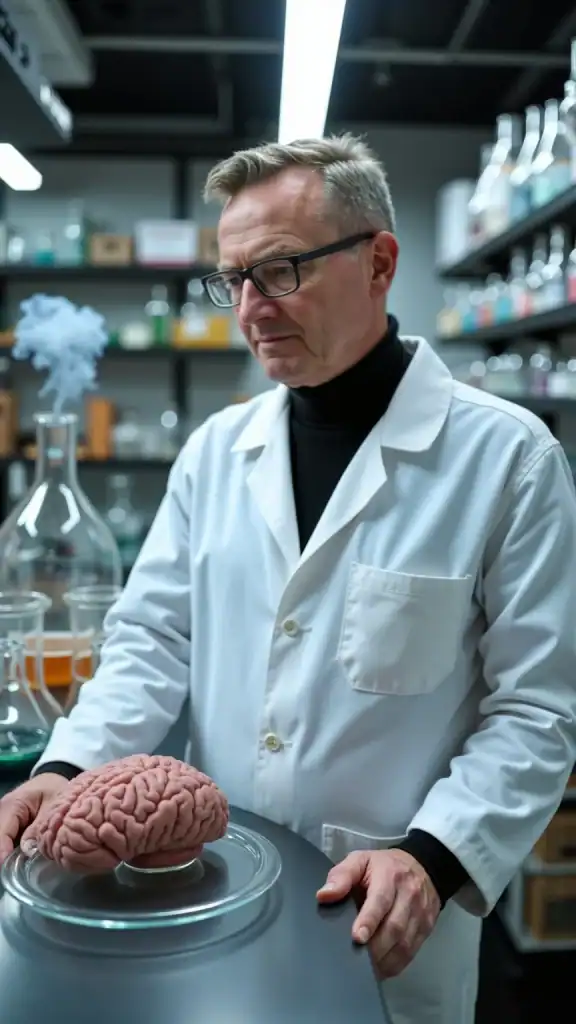

(Featured picture: Good old Sigmund Freud)

And why not ask good old Freud

Yes, Sigmund Freud and his daughter Anna developed the theory about psychological defence mechanisms. Verywellmind.com describes a defence mechanism as:

Unconscious psychological responses that protect people from feelings of anxiety, threats to self-esteem, and things that they don’t want to think about or deal with.

But why should our minds try to protect us from ourselves? After all, most of us would agree that it’s not a good solution to bottle up painful experiences inside ourselves. In fact, bottled-up things tend to be preserved. They won’t go away.

The practical solutions of the mind

According to Freud, defence mechanisms are a way for the mind to resolve (or suppress) conflicts between the id (the animalistic aspect of us) and the superego (the moralistic aspect of us).

Let that be as it is; for me, it makes sense that our minds might try to cover things up now and then. For at least three reasons:

- The conflict may not be only in our minds. Sometimes, we must live with conflicting expectations from others that are difficult to resolve.

- Whether it is based on reality or not, our brains might find the situation at hand so stressful that its priority is to survive. How we feel about it will have to wait.

- Shame. Oh yes, good old shame. We are so ashamed of being who we are and thinking and feeling what we do that we just can’t relate to it.

You can read more about the defence mechanisms from psychodynamic theory here:

What follows is a selection of defence mechanisms that I can connect to personal experiences. If you have ever struggled with figuring out what you really feel and why you react and act like you do, you might also find some of them surprisingly familiar.

Oh, before we start…

Remember when you read about the defence mechanisms that there’s nothing wrong with you if you recognise yourself in them. They’re not diagnoses; we’re not talking about disorders here.

They are simply a way to describe our common human ways to relate to our emotions. We all employ many defence mechanisms to a greater or lesser degree, in a more or less healthy manner, at times.

However, if we are on a journey trying to leave our anxiety or depression behind, understanding what we really feel is essential. That’s what this is about. To know enough about our own defence mechanisms to look through our minds’ smokescreens and see what’s going on.

The leaders of the gang

These two defence mechanisms are slightly similar but also different:

#1 Repression

Involuntarily/unintentionally blocking upsetting feelings from entering the consciousness. Repression hides thoughts, feelings, and fantasies from consciousness, leading to forgetting and/or denial.

– Psychdb.com

#2 Suppression

Putting unwanted feelings aside to cope with reality.

– Psychdb.com

While both aim to keep upsetting things out of our conscious minds, we can also see a significant difference. When suppressing, we make a conscious choice to keep them out. When repressing, our brains attempt to keep it out of our attention altogether.

Suppression can be a helpful mechanism when coping with critical situations if emotions such as fear must be put aside until circumstances are under control. I nearly fell off a cliff at the age of 12 and was saved by a scrawny bush growing on the cliff’s edge. I also went off the road once in a military vehicle while doing my National Service. On both occasions, it was beneficial that the emotional reactions could be addressed on stable ground afterwards.

However, we must allow our emotional reactions to be expressed in due time. This is why personnel from the police, fire brigades, and military forces are now offered debriefing after high-stress incidents. Or, at least, they should be.

Repression, on the other hand, is more likely about experiences so horrible that we struggle to relate to them at all. I also believe memories can stay repressed after being actively suppressed for a while. For instance, while exploring my mind, I sometimes come across memories I’m pretty sure I haven’t remembered this side of 1980.

What repression and suppression have in common is that they often recruit other defence mechanisms to help keep the upsetting things out of our conscious minds.

Refusing reality

#3 Denial

Behaving as if an aspect of reality does not exist.

– Psychdb.com

Oh, yes, we can easily deny the existence of the troubling emotions themselves, the situations that caused them, and even deny our behaviour resulting from what has happened.

As I recently wrote in my article The distant song of a forgotten child, I spent a long time trying to psychoanalyse myself out of mental injuries from my childhood while I completely denied the problems in my then-current life.

The challenges of addressing the issues in my then-current life seemed insurmountable, so my brain took the easier path; it denied the existence of the problems right in front of me.

The loud and quiet anger

#4 Acting out

Easing unacceptable feelings by behaving badly.

– Psychdb.com

I cannot help thinking of my father’s explosive anger and how I tiptoed around most of my childhood, trying to avoid it. And I’ve met so many other people, primarily men, who use anger the same way, presumably to avoid dealing with other uncomfortable emotions like insecurity, sadness, or guilt and to gain an advantage by scaring others into submission.

Of course, anger isn’t the only way to act out. Oh, there are many ways to ‘break the rules’: legally, financially, sexually, you name it. I found my ‘acting out escape’ in periodically heavy alcohol consumption. Still, for me, as I believe it is for many others, there was a hidden anger and shame underneath. I felt inferior and not good enough; I was angry and ashamed about it, but I couldn’t show it, so I acted out instead.

Complicated matters, you know.

#5 Passive aggression

Avoiding conflict by expressing hostility covertly

– Psychdb.com

I spent a lifetime with a then-partner who was an expert in showing restrained anger in a thousand different ways: the silent treatment, sullenness, sarcasm, criticism, guilt-tripping, vague complaints, double communications (for instance, saying positive things in a bitter, resentful tone of voice).

She didn’t have to copy my father’s explosive anger to subdue me. This work could be done in a much quieter way by undermining my self-esteem in myriads of ways every day. And I was thoroughly conditioned by my childhood to avoid conflict, which likely only made the situation worse for both of us.

It took me a long time to come this far, but I don’t think now that she behaved that way on purpose. It was probably just a way for her to manage her own insecurities.

However, even though we all sometimes do it unconsciously, it’s not a human right to harm others just to feel better ourselves. It can happen in the heat of the moment for all of us, but in the long run, we do have a choice and a moral obligation to question and adjust our behaviour.

Just trying to be rational

#6 Rationalisation

Justifying behaviour to avoid difficult truths. The ego addresses unacceptable feelings by coming up with reasons or justifications.

– Psychdb.com

Early in my career, I changed jobs frequently, approximately every two years on average. I felt I had good reasons every time, and I could quite rationally explain why each job turned out unsuitable for me.

My arguments mostly fall apart when I look at them in hindsight. The jobs should have been reasonably manageable, except perhaps when I took on sales roles. I’m probably the least talented salesperson imaginable.

Anyway, why did I do this? Have a look at defence mechanism #8 (Displacement).

#7 Intellectualisation

Using facts and logic to avoid uncomfortable feelings. […] this defense uses excessive thinking to replace painful or uncomfortable feelings.

– Psychdb.com

I’ve always had pretty strong analytical abilities. When I was in therapy 15-20 years ago, I apparently saw this as a trait I could use to my advantage and spent the therapy sessions meticulously analysing my childhood and youth (while I, as mentioned, blankly ignored my then-present life). Most of my intellectually achieved conclusions were correct enough.

The problem is that, at best, I was only doing half the job. There was never anything wrong with my logic or reasoning. They were not what I needed help with. What needed attention was myriads of old and new trauma, ghosts from the past and the present, anxiety and non-existent self-esteem.

Analysing was much less terrifying, though, so that was what I spent the time doing while I was in formal therapy.

Us and them

#8 Displacement

Redirecting one’s feelings or impulses to a neutral person or more acceptable object.

– Psychdb.com

To recap, I was frequently changing jobs early in my career. Well, what I really needed was a change in entirely other areas. I desperately needed to do something about both my mental health situation and my private life.

However, blaming my work was, of course, easier to explain and less scary to go through than having a major confrontation about the relationship I lived in or addressing my mental health problems.

#9 Idealisation

Idealisation involves creating an ideal impression of a person, place or object by emphasising their positive qualities and neglecting those that are negative.

– Psychologistworld.com

Speaking of the relationship I lived in, I didn’t let any criticism of my then-partner come into consideration of what was wrong in my life. How could I? She put up with me, didn’t she, despite all my flaws? I just had to be grateful!

In this way, I repeated the mantra I had learned in early childhood: I was worthless, despicable, and unloveable, and I willingly allowed others to reinforce this belittling image of myself. Why? I would do anything to avoid conflict. Even convincing myself I deserved nothing but contempt and that others were right to detest me.

Because then I didn’t have to stand up for myself, right?

#10 Introjection

Introjection occurs when a person takes stimuli in their environment and adopts them as their own ideas.

– Psychologistworld.com

And this is precisely what happens, you know, when we’re living in toxic relationships.

Day by day, the constant criticism and sarcasm soak into us. Every time the room unexpectedly drops into deadly silence or explodes with anger, every time we come home and somehow feel that doom is waiting before a single word is said, every time we cave in and admit it’s all our fault, our worldview is shaped to accept the one and only truth:

We are to blame. Always. Because there’s something inherently wrong with us. And there’s a kind of perverse freedom in realising this, believing in it, because then we don’t have to fight against it anymore.

#11 Identification

In order to pacify a person whom we perceive to be a threat, we may emulate aspects of their behaviour. By adopting their mannerisms, repeating phrases or language patterns that they tend to use and mirroring their character traits, a person may attempt to appease a person.

– Psychologistworld.com

Oh, and sometimes, we do this to appease a whole family or community, don’t we? Because if we don’t, we’re the odd ones. And in many families or communities, the ones who don’t entirely ‘fit in’ are the ones who will end up at the bottom of the pecking order.

So, we instinctively try to fit in, and it happens stealthily and gradually. Mostly, we won’t notice that we are ‘becoming them’.

I remember waking up from it once. In the sense of suddenly realising how the culture I grew up in had infected me. I was talking about someone, probably just a random person who never had done me much wrong, and I noticed my tone of voice. This was in the mid-1990s, but to my own surprise, I still used the bitter, sarcastic, derogatory tone of voice I had learned in my childhood.

And I realised this wasn’t my voice. If I listened, I could hear other people sounding like that in my memories —people in my family and from my childhood community. This wasn’t me, and I didn’t want to be like them. The realisation was both a shock and a huge relief.

#12 Projection

Attributing one’s own feelings to others. The ego protects itself by perceiving unacceptable thoughts, feelings, and fantasies as originating outside of the self.

– Psychdb.com

I have a memory of discussing certain people with a then-friend of mine, and he said, “You just have to give them the benefit of the doubt.” I must have been 19 or 20 back then, and I said something like, “No! To me, everyone is a bastard until the opposite is proven!” Even though I believed I had good reasons to feel like this, I can still remember my friend’s expression as I said it.

I was in a terrible state at the time, and I believe I must have been on the border of paranoia. Most likely, I had so much fear and anger bottled up inside me that I couldn’t relate to it all anymore. To protect myself, my mind decided that everyone else was aggressive and unreliable and likely to attack me anytime.

Which wasn’t and isn’t true, of course. Yes, there are mean bastards out there, but they are few. And there are angels and saints in human shape out there as well. And the majority? Well, the truth is that they don’t care about us at all. They are way too busy with their own life and worries. We are just someone who passes through their lives just like they pass through ours.

Realising this gave me much less to worry about.

#13 Reaction formation

Behaving in a manner opposite to one’s actual feelings.

– Pshychdb.com

It’s important to remember that this doesn’t mean choosing to behave in a manner opposite to one’s actual feelings. This is our mind automatically protecting us by hiding what we actually feel from ourselves and causing us to behave oppositely.

I once was in a relationship with a person who consistently displayed a rather aggressive and hostile attitude toward most of my friends. Not face-to-face the few times she met them but in conversations with me about them. There were no limits to the amounts of flaws she saw in their characters and behaviours, even though, in reality, she didn’t know much about them.

It took me some time (a few decades) to understand that she must have had a serious jealousy problem. And this, perhaps, didn’t fit into her need to feel superior because jealousy is about being vulnerable, most likely about fear of abandonment. Aggression was a much more acceptable emotion for her to feel and express.

Emergency exits

#14 Fantasy

Tendency to retreat into fantasy in order to resolve inner and outer conflicts.

– en.wikipedia.org

Oh, if we could only replace reality with times, places, and situations where its problems don’t exist, or if they do, we have the power and courage to solve them.

My imagination was my place of refuge from a very early age. That’s probably why it’s relatively well-developed. And from the moment I learned to read, books were my sanctuary. I devoured almost everything printed on paper, both fiction and non-fiction, including atlases and encyclopedias. At the age of sixteen, I was introduced to J.R.R. Tolkien’s universe, and I wished his books would never end!

I would say this is the healthiest form of escapism I have engaged in. You might disagree, but I would also categorise my alcohol consumption in my younger years as a kind of fantasy and not quite as healthy as books.

My drinking was also about retreating into a fantasy world where the booze made the world a little less scary and me a little braver. At least I could feel more courageous for a short while.

I’m not proud of how my drinking habits were in periods. However, this is not a black-and-white picture. Without anything else to lean on, alcohol gave me the brief breaks I needed and perhaps wouldn’t have survived without.

#15 Regression

When a person reverts to the types of behaviour that they exhibited at an earlier age.

– Psychologistworld.com

Speaking of alcohol. I believe my tendencies, until recently, to fall back into old drinking habits when I was stressed may be classed as regression.

I was introduced to alcohol around the age of thirteen. I was still decades away from acknowledging or even understanding I had an anxiety problem because I had never experienced not feeling stressed and anxious. I was 27 years away from trying any medication or therapy. In fact, I had no one to talk to at all.

The immediate anti-anxiety effect of alcohol was a shock for thirteen-year-old me, a positive shock. Although I soon learned that everything, including my anxiety, got worse when I was hungover afterwards, alcohol was my only comfort for years to come.

It’s not strange, perhaps, that I regressed myself drunk many times when I felt overwhelmed enough to believe the world was still as chaotic as it seemed to me when I was thirteen. Even after I knew much more about anxiety and depression, treatments for them, and even after I eventually found someone to talk to.

#16 Sublimation

Channelling impulses and emotions into more socially acceptable behaviours.

– Psychdb.com

For decades, I channelled most of my energy into work. I wonder if this, at least partly, could be labelled as sublimation. Yes, it was also partly fear-driven, I always worked 150% to avoid anyone finding any flaws in me or what I did.

However, I also found some joy in my work, as opposed to my private life. Dedicating myself fully to my work was also, undoubtedly, a form of escapism for me.

#17 Somatisation

Transforming emotional conflicts into physical symptoms. Here a thought or affect is repressed and is experienced as a bodily sensation.

– Psychdb.com

We have all felt our anxiety like a dagger stabbed through our solar plexus, haven’t we? Or depression like a heavy stone in our bellies.

Let’s add muscle pains, headaches, dizziness, fatigue, numbness in the limbs, trembling, nausea and indigestion, a failing immune system, insomnia, you name it.

Yes, I guess it may happen that our minds subconsciously ‘transform’ anxiety or depression, for instance, to physical symptoms. After all, it’s still more acceptable and way less shameful to have a physical problem than a mental one.

However, we’ll have to be careful about saying that our physical symptoms are something our brain has ‘made up’ to protect us. Living in constant stress means our brains and bodies are constantly flooded with stress hormones, which, over time, may lead to various and very real physical conditions of the kinds mentioned above.

#18 Humour

Using humour to avoid uncomfortable feelings.

– Psychdb.com

I don’t know if I can call it humour, but I remember using laughter as a mask in certain very uncomfortable situations. Particularly when being forced to observe people arguing. This used to trigger a strong anxiety reaction in me because of unfortunate childhood experiences.

Instead of removing myself from the situation or asking people to behave themselves, I often found myself laughing. Humour? Not really. It was just an attempt to distract myself, and perhaps others, from the uneasiness of the situation.

‘Gallows humour’, on the other hand, is something two or more people can share under challenging circumstances and is often an inspiring and healthy coping mechanism as I see it.

Other sources of confusion

Apart from the defence mechanisms described in psychodynamic theory, here are a few more reasons why it can be hard to identify what we really feel:

#19 “I don’t know how to describe it…”

Yes, it is hard to identify and relate to something we cannot put into words. Of course, there may be many reasons why we cannot describe what we’re feeling. Perhaps we’re in a situation we’ve never been in before. Perhaps we lack the emotional vocabulary because we feel something that we simply don’t talk about in our culture.

There is even a psychological term, alexithymia, which refers to difficulties in identifying, understanding, and expressing emotions.

In the course of my own self-exploration, I have also come across memories that defy description, more sensations than images in nature. My theory is that these are very early memories from a time before I had language, and therefore, they are impossible to recount in words.

#20 “I can’t take anymore…”

Cognitive overload kicks in when too much is happening at the same time, too much stress than we can handle, and we just have to try to survive. We can’t think. Sometimes, we can hardly move and breathe.

How can we know exactly what we feel under circumstances like these, with our brains gone totally blank?

#21 “I have mixed feelings about this…”

Children up to a certain age have problems feeling different things at the same time, for instance, simultaneously loving and fearing an unpredictable parent. Living with such a parent can, of course, be quite damaging for a child.

As adults, however, we are better equipped to hold two contrasting thoughts in our heads simultaneously. For instance, we can more easily admit that our (now ageing) parents can be both lovely and challenging at times.

Still, sometimes conflicting emotions can make it harder to determine what we genuinely feel, especially if one feeling is culturally less acceptable than the other.

Remember what I said earlier!

There’s nothing wrong with you if you (mostly unconsciously) use defence mechanisms to protect yourself from uncomfortable thoughts and emotions. I’m not pointing fingers at you! As you’ve seen above, that would mean I’m pointing most of those fingers at myself.

However, understanding what we truly feel is key to getting anywhere on our journey out of anxiety or depression. My point is that getting to understand what we truly feel isn’t necessarily simple and easy.

As with everything else you encounter on the mentioned journey away from anxiety and depression, this requires patience and a good portion of self-compassion. Sometimes, we just have to walk in circles for a little while to find where to go next.

Remember, we are trying to troubleshoot the most wonderful but also the most complex system in the known universe: The human mind.

All illustrations used in this article are AI-generated. Some of them resemble me at different ages, but they aren’t real pictures.

Post Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.