The decision is Lillehammer!

The president of the International Olympic Committee, Mr Juan Antonio Samaranch, said this when he announced that Lillehammer, Norway, was chosen to arrange the 1994 Winter Olympics. This happened on the 15th of September 1988, and I had left the Lillehammer area just a few days before.

Actually, what Mr Samaranch said sounded more like “the decision is Lilyhammer”, which later inspired the creation of a Netflix series in which a famous musician played a gangster instead of the guitar.

I’ll return to this. However, our decision was also Lillehammer when we wanted to make a tourist stop somewhere on this year’s trip to Trondheim to visit my family. On the other hand, my first stay in this area wasn’t entirely a matter of choice.

(Featured picture: Tom’s wife and bonus daughter on a footpath crossing over the river Mesna in Lillehammer, Norway.)

“You’re in the Army now, whoooooo, you’re in the army, now”

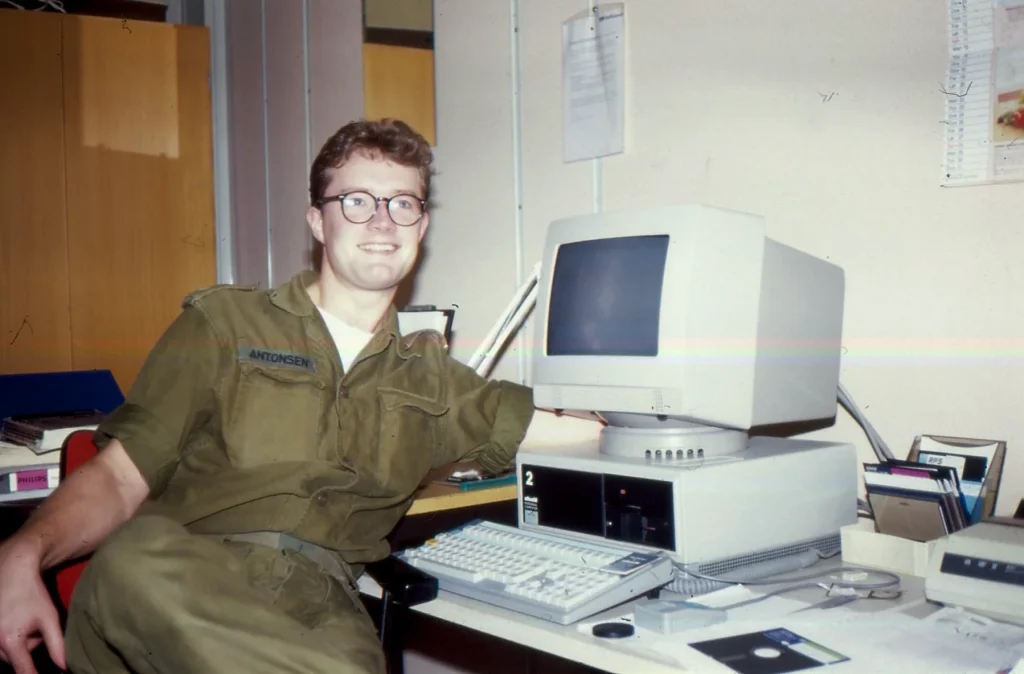

Well, this was Status Quo’s hit from 1986. It was my turn the year after, in 1987. National Service was mandatory in Norway back then and still is (in principle), but today’s high-tech Defense Forces don’t need everyone to serve. In the 1980s, ‘mandatory’ still meant ‘everyone’, at least every young man, unless he could solemnly swear he was a pacifist. In that case, they would find a civilian service for him, something undesirable enough to deter others from refusing military service.

Anyway, I was a child of the Cold War. Even though the thought of taking lives was highly problematic for me, I decided I would choose to defend my country if a war situation with the Soviet Union dictatorship came to pass. Which meant I couldn’t declare myself a pacifist.

Most young men did their National Service directly after finishing college. For some practical reasons, mine was postponed for three years while I did my university education in electronics and worked my first year as a teacher. Luckily, this background made me eligible for a relatively pleasant and interesting year of National Service near Lillehammer.

A sleepy old town

Although the Army camp was situated a few miles away, we sometimes took the bus into town for necessary maintenance, such as getting an appropriate haircut or indulgently drinking a beer or two if our very meagre soldier salary allowed it.

I liked Lillehammer. It was smaller, of course, than the city of Trondheim and felt calmer. Almost a bit sleepy.

It was probably true that this town, with its population of about 20,000, was slightly hibernating in the late 1980s. Positioned at the northern end of the more than 60-mile-long lake Mjøsa, Lillehammer was traditionally a local centre of trade and transport, connecting boat traffic on the lake with inland transport northwards through the mighty Gudbrandsdalen valley.

The Dovrebanen railway line between Oslo and Trondheim was completed in 1921. Lillehammer was still one of the many stops along the way, but perhaps more of a town people passed through now.

Then, as the 1960s turned into the 1970s, Norway entered the oil age, and my country of birth was changed forever. However, the oil economy was primarily coastal, and inland Norway was left behind.

What can you do if your region is a stagnant backwater? Any ideas? Apply to arrange the next Winter Olympics, perhaps?

The decision is Lillehammer

Ten days after I left the Army to return to Trondheim and continue my education, Juan Antonio Samaranch jolted Lillehammer out of the backwater with his now famous announcement (at least, it’s renowned in Norway).

A tiny town in a small country had six years to prepare for one of the planet’s most significant sports events. They made it happen, and I believe they impressed the whole world.

I briefly returned to Lillehammer for an Army follow-up rehearsal shortly after the Olympics. The road infrastructure had been heavily upgraded, and when navigating using my pre-Olympic memories, I could hardly find my way in and out of the town. Luckily, however, the now envigorated Lillehammer kept its small-town charm.

The Godfather of Lilyhammer

I didn’t pay much attention when Lillehammer gained international fame again in 2012. Big things were happening in my life at the time. Hard things. I had no time or energy to spend on light-weight TV comedy.

However, as an above-average music-interested person, I noticed that the Netflix TV series Lilyhammer, set in (yes) Lillehammer, was fronted by Steven van Zandt, more known by his stage name Little Steven, guitarist in Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band.

Then, life took its twists and turns. Twelve years later, I was living in England with an English wife who is interested in learning about Nordic cultures (probably to understand her strange, foreign husband better). We explored films and series from Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, and Iceland and stumbled upon Lilyhammer.

I realised the series was a good satire, obviously written by Norwegians to make fun of Norwegian mentality and culture in general. It can be recommended for everyone who wants a humorous view of us Norwegians. However, I advise international viewers to find a ‘local guide’, as my wife had, if they want to understand every cultural peculiarity made fun of.

Being tourists in Lillehammer, 2025

I’ve passed through Lillehammer many times since the 1980s. I’ve even spent the night a few times cutting the long drive from Oslo to Trondheim into more manageable pieces for small children in the backseat. But I’ve never taken the time to be a real tourist there until now.

We visited the Norwegian Olympic Museum and the cultural history museum Maihaugen, Norway’s largest open-air museum.

The United Kingdom isn’t the most prominent winter sports nation. Nevertheless, my English wife actually remembers the 1994 Winter Olympics because Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean won a bronze medal in figure skating. The UK also earned a bronze medal in 500 metres short-track speed skating.

I’m not competitive at all, so I won’t mention that Norway collected 10 gold, 11 silver, and 5 bronze medals.

The Maihaugen Museum covers a considerable area and has both indoor and outdoor exhibitions. Numerous old buildings built over the centuries were rescued from demolition, carefully dismantled, and rebuilt on the museum grounds. Visitors can enter some of the buildings to see original furniture and utensils.

My wife and I had hoped that the museum’s 1970s and 1980s houses would be accessible with authentic interiors for nostalgia reasons. This would kind of have been our childhood and youth on display. However, to our slight disappointment, these houses were shut off.

Anyway, visiting the museums is highly recommended if you stop by Lillehammer one day.

The decision might be Lillehammer again

Leaving Lillehammer behind, the train took us up the Gudbrandsdalen valley towards the majestic Dovre mountains and Trondheim beyond them. This departure felt like a promise of a return.

I have lived on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean in Norway and England most of my life. Surprisingly, the surroundings of Lake Mjøsa and the Gudbrandsdalen valley seem much more familiar to me than the time I’ve spent there can explain. I feel a serenity there I haven’t felt in other landscapes.

We have talked about possibly moving to Norway when we retire. Right now, Lillehammer seems like an excellent prospect for a future home.

Goodbye, for now, Lillehammer. Just wait a while. The decision, our decision, might be Lilyhammer once again.

Post Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.